The financial markets today and the Paradox of Tranquility

Despite a slight pick-up in volatility over the last nine months, the equity and bond markets are very calm. Equities and all forms of bonds have been steadily rising since 2009. Every time they go down, there is a flood of buying interest.

Isn't this a sign that everything is fine? Actually no, it isn't. Equities are rising and credit spreads are falling not because the economy is in rude health and growth means a rising share to everyone. They are rising because investors are becoming more and more willing to accept a lower yield on the understanding that

- Growth is going to be bad.

- There exists a 'Central Bank Put' which will continue to add money to the system in the case of any downturn.

Paradoxically the lower economic growth is leading to a rise in asset prices because it is leading people to expect and accept lower yields. High corporate profits as a share of GDP give an illusion of good returns for equities, however they are a symptom of the malaise that has driven salaries down and thereby stunts future economic growth by increasing structural savings.

Allied to this, there is the feeling that the thus far infallible central bank will always bail them out if something goes wrong. Their share of the future economic pie is protected. Their savings are invincible.

There is, however, a flaw in this argument. The central bank is not infallible, and in fact is reaching the limits of its influence.

So far, this fallibility has not been tested as there has always been a tool that the central bank could use to save the markets. The fact that there has always been a way in the past gives confidence to people that there will always be a way in the future and this will make the fall even more painful.

The tranquility that we see in the market, as I discuss here, is based on a chimera. It is true only because everyone believes it to be true and will continue to be true as long as that belief holds. But the confidence engendered by this tranquility has only sown the seeds for the mess that awaits us. The more confident everyone is before the crash, the bigger the crash will be.

The solution to this mess (in terms of the economy at any rate, if not the markets) will be Central Bank money given directly to the government, but unfortunately I fear that this solution will be avoided for as long as possible causing untold economic damage.

In order to explain why the central bank has reached its limit, I will once again invoke my Cash Flow model of the economy. It is first summarised and then the important part discussed.

Flows model

The basic model was originally presented here but a summary is below:

Demand Based Cash Flow Model of the Economy

A very simple static model of a closed system will be presented, ignoring, among other things, the government and the financial sector as well as any investment. This will suffice to illustrate the basic idea and draw important conclusions. In this model the economic product (GDP) of time period t creates cash flows. The total of the GDP is paid out either as wages to workers net of mortgage, interest and rental payments (w), interest to bond holders and banks (i) and dividends and rental payments to landlords (d).

Each receiver of their share of GDP then has their own marginal propensity to consume, α .

There are other sources of spending that are not from the previous period's GDP. The first is spending of existing savings (ES); people or corporations that have previously saved up money will spend a proportion (γ) of these savings during this time period. The second is Net New Loans (L); this is subdivided into government (LG) and private-sector (LP). When a loan is created, a certain proportion (also denoted by α) will be spent on goods and services. This would almost certainly be higher for government loans than for private sector loans. The third other source of spending is new cash created by the central bank (C), which also has its own α.The equation for GDP at time t+1 is thus given as:

GDP(t+1) = αd*d + αi*i + αw*w + αLG*LG + αLP*LP+ αC*C + γ*ES (1)

where

GDPt= d + i + w (2)

Now, in a fully healthy economy, with expected trend growth of gt% and inflation rate of it%, we would see the following:

GDP(t+1) = (1 + 0.01*(gt + it))*GDPt (3)

This is to say that GDP should increase by inflation and growth each year.

Under ideal circumstances this would be achieved without the help of either further private sector or public sector debt. So equation (1) would become:

GDP(t+1) = αd*d + αi*i + αw*w + αC*C + γ*ES (4)

However, for a very long time now, the right hand side of equation (4) has been unable to be high enough to suffice for equation (3). That is to say that there is structurally not enough spending and too much saving in the economy. I call the gap between the right hand side of equation (4) and the right hand side of equation (3) the 'demand gap'.

How, then, was such high economic growth achieved between 1945 and 2008? The demand gap was largely filled by increasing private sector debt. I estimate here that in the period since 1995 approximately 11% of new private sector debt was spent in the economy in the year it was taken out. As an average of 10% of GDP per year has been taken out, this means that approximately 1.1% of economic growth per year can be attributed to private sector debt filling the demand gap.

This is the predominant, but not the only mechanism that the demand gap was filled. Looking at equation (1) for clues suggests other ways. Equities and bonds have been on a long bull market. This means that existing savings (ES) have been continually rising, giving savers more money to spend. This wealth effect helps to fill the demand gap.

At times when the private sector was unable or unwilling to fund the gap, the government has stepped in, increasing LG.

What happens in an economic downturn?

Looking at equation (1), there are a number of ways that GDP is affected by a downturn. I will use 2008 as an example as I believe that it is a template for what could happen next time.

The first problem is the credit crunch. This means that LP goes negative. More loans are recalled than given. This brings down GDP.

The second problem is that people lose confidence and save more. Thus all the α values and the γ go down. This also significantly brings down GDP.

Equities crash and credit spreads increase, causing ES to go down, thus also having an impact on spending. If people are poorer they will spend less.

Then the feedback loops begin. As demand goes down, workers are made unemployed. This reduces the value of w, thus shrinking demand further.

If fiscal and monetary policy does not apply stabilisers to this then, as in the early 1930s in the US, this downward spiral can continue until a new, much lower equilibrium is reached.

Fiscal and monetary stabilisers

This is where the government does its part. Government borrowing increases; some naturally in response to lower tax receipts and higher welfare payments, some deliberate. The increase in LG helps to counteract the falls described above.

At the same time, monetary policy kicks in. A reduction in interest rates stimulates further private sector loans, LP.

Up to 2008, this all worked just fine. Unfortunately by 2008 the levels of private sector debt were just too high to stimulate more of it. Interest rates hit the zero lower bound but the poor state of the economy meant that even at these low rates net new debt was not being taken out.

Next came Quantitative Easing. By swapping one form of money (government debt) for another (cash) this is not really printing new money. The large amount of cash swapped for government debt had only a small impact on GDP. This impact came from two main sources.

First, it led to a reduction in long term bond yields which pushed up asset prices. Thus ES went up and spending in the economy marginally increased.

Second, the low long term bond yields helped to stem the decline in private sector loans.

These are both second order effects, hence the small impact but still there was some improvement in growth in the years of QE.

But what happens next time?

Look at the situation now. We have just had a huge rally in equity and bond prices. Long term bond yields are hitting zero. Credit spreads have shrunk in a desperate scramble for yield. Equities look overpriced by any historical measure. The only way that these prices are justified is if the economy can be kept stable by the central bank.

But it can't.

I don't know when the trigger will come, or what it will be. It could even be years away but I don't think it will be that long. At some point we will get a trigger. Liquidity in the markets is much lower than it has been and especially in higher yield bonds if a crash starts there could be no buyers. The first reaction to a drop may be for buyers to come in. But there will be a time when the buyers will not be there and the drop will continue.

Now, panic will arise. It will spill over into other asset classes as market participants are forced to liquidate positions taken out during a time of false confidence. The feedback effect of this will cause a market crash as people will be unable to hold their positions in the high volatility, low liquidity environment.

The credit markets will dry up and the process described above in the crash scenario will begin to unfold.

People will be asking where the Fed put is now? What can it do to stem the crisis?

Interest rates can't be lowered. They are already almost at zero. Quantitative Easing has very limited impact at the best of times, but with long term government bond yields so low already, the long term interest rates can not be reduced much further.

It may decide to buy corporate debt in an attempt to keep these yields lower; but once again the effects are limited.

In fact, the central bank has reached the point where it has very little ammunition left. The full force of the adjustment will need to be carried out by the government using fiscal policy. Since governments in the UK and US are already running a deficit and since monetary policy can't help, the government will have to run deficits at 15%+ of GDP.

The problem here is that government debt to GDP is already, in many countries, running at approximately 100% of GDP. There will be political pushback from politicians who don't understand economics to this level of spending.

All in all, next time we crash, the starting point will make an appropriate response very difficult to achieve.

The Solution

The solution is to allow the central bank to give government enough money to hit its inflation target. It could be structured as an interest free loan but the best solution would be one that the government can not see this debt at all as it avoids politicians' tendencies to worry about debt problems that are not there.

Looking at equation (1) above, this is the only way that the structural demand gap can be filled without further debt being taken out.

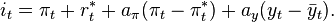

is the target short-term

is the target short-term  is the rate of

is the rate of  is the desired rate of inflation,

is the desired rate of inflation,  is the assumed equilibrium real interest rate,

is the assumed equilibrium real interest rate,  is the logarithm of real

is the logarithm of real  is the logarithm of

is the logarithm of  and

and  should be positive (as a rough rule of thumb, Taylor's 1993 paper proposed setting

should be positive (as a rough rule of thumb, Taylor's 1993 paper proposed setting  ).

).